The Complex Intelligence of Orcas

A Case for Freeing Kshamenk

Three orcas or killer whales by Jeroen Mikkers

Orcas (Orcinus orca), the ocean's apex predators, dominate the marine food chain through their extraordinary intelligence. A striking example of this intelligence is their complex social behavior, characterized by intricate vocal dialects, much like those of other cetaceans. Living in matrilineal pods, each group develops unique calls, comparable to distinct dialects within a human language, which evolve through their remarkable ability to mimic sounds.

A captive orca named Wikie exemplified this by effortlessly imitating human words and animal calls, demonstrating the species' cognitive sophistication.

Like humans, orcas exhibit selective feeding habits, with certain populations targeting specific prey parts for their nutritional value. Some orcas have mastered the art of hunting sharks, such as great whites off South Africa or whale sharks near Mexico, exclusively for their nutrient-rich livers, discarding the rest of the carcass. This strategic behavior highlights their sophisticated hunting techniques and discerning food preferences.

Grieving mother orca carries deceased infant calf neonate’s face (above). This baby Southern resident killer whale (SRKW) died a short time after it was born near Victoria, British Columbia on July 24, 2018, Photo by Michael Weiss, Center for Whale Research.

Orcas exhibit profound grief and mourning behaviors when pod members pass away, revealing their deep emotional capacity. Researchers from the Center for Whale Research have documented heart-wrenching instances of orcas seemingly grieving.

In one poignant case, a female orca named Tahlequah carried her deceased calf for 17 days across 1,600 kilometers, a powerful display of mourning before she finally released it. Such behaviors are characteristic of highly social, long-lived mammals and underscore the strength of their emotional bonds.

Tragically, the Southern Resident killer whale population, classified as “Endangered” for the past two decades, has faced devastating losses, with approximately 75% of newborns failing to survive infancy. Over the last three years, every pregnancy within this population has resulted in the loss of viable offspring. Further research is urgently needed to uncover the causes of these alarming trends and to support the survival of this iconic species.

The Whale and Dolphin Conservation charity emphasizes that researchers have extensively documented various whale and dolphin species carrying their deceased calves or juveniles, a behavior demonstrating profound mourning. These displays of grief are prevalent among social, long-lived mammals, reflecting deep emotional connections. Historically, the scientific community has approached terms like “grief” with caution, wary of anthropomorphism. Yet, a growing body of evidence reveals that cetaceans, elephants, and many other animals across the animal kingdom exhibit emotions closely resembling grief, offering compelling evidence of their sentience.

Recognizing these remarkable emotional capacities in non-human species is long overdue, yet commercial hunting and exploitation of these creatures persist. Acknowledging their sentience carries profound implications for industries economically tied to their exploitation, urging a critical reevaluation of humanity’s relationship with these fellow beings.

Dolphins have in the last decade recently achieved legal recognition as persons, acknowledging their sentience. This crucial step should be extended to encompass all cetaceans and a wide range of other animals within the animal kingdom. Dr. Thomas White´s book ´´In Defense of Dolphins: The New Moral Frontier´´, lays out overwhelming evidence on the topic of Dolphin Sentience, where he successfully presented the case for extending personhood recognition to these remarkable creatures and beyond is compellingly discussed. See his science paper on Dolphin People . Listen to my Interview with Dr Thomas White.

Killer whales, or orcas, boast remarkably large brains, weighing up to 15 pounds, finely tuned for navigating and interpreting complex underwater environments through echolocation. According to NOAA Fisheries research, certain orcas demonstrate an extraordinary ability to differentiate between fish species by detecting subtle acoustic signatures, such as the distinct size and orientation of salmon swim bladders, showcasing their advanced cognitive and sensory capabilities.

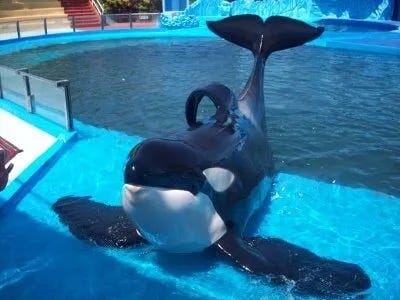

Humans have trained captive orcas for various purposes, including performances at places like SeaWorld, which we hope will be ceased. While the ethics of keeping orcas or any cetacean in captivity for entertainment purposes remain a subject of debate, the evidence shows that life in captivity for orcas causes suffering, early mortality, disease and loneliness, their capacity to learn and execute tasks as trained demonstrates their immense cognitive abilities.

Orca Family Pod by Michael Zeigler.

Killer whales, or orcas (Orcinus orca), exhibit a remarkable array of social behaviors that mirror human social customs, with one of the most striking being their “greeting ceremonies.” These intricate rituals highlight the depth of their social intelligence, emotional connections, and cultural complexity, reinforcing their status as highly social marine mammals. Below is an elaborated exploration of orca greeting ceremonies, their significance, and their parallels to human social practices, incorporating insights from scientific observations and the broader context of orca behavior.

The Nature of Greeting Ceremonies

Greeting ceremonies are formalized social interactions observed primarily among resident orca populations, such as those in the Pacific Northwest, though similar behaviors have been noted in other groups. These rituals typically occur when two or more pods—tight-knit family groups centered around a matriarch—encounter each other after a period of separation or during significant social events, such as reunions, births, or seasonal gatherings. The ceremonies are characterized by highly coordinated and theatrical displays that serve to reinforce social bonds, establish group cohesion, and possibly communicate pod identity.

In a typical greeting ceremony, orcas from different pods align themselves in two parallel rows, facing each other in a structured formation. This alignment is often described as resembling a formal greeting line or a ceremonial procession. Once positioned, the orcas engage in synchronized behaviors, including:

Synchronized tumbling and diving:

The orcas perform coordinated flips, rolls, and dives, creating a dynamic, almost choreographed display. This has been likened to a “mosh pit” due to its energetic and communal nature, with individuals moving in unison or in complementary patterns.

Vocal exchanges:

The orcas emit a variety of vocalizations, including clicks, whistles, and pulsed calls, which are unique to each pod’s dialect. These sounds likely serve to reaffirm pod identity, coordinate the ritual, and express excitement or recognition.

Physical contact:

Orcas may gently nudge, rub, or swim closely alongside one another, reinforcing social bonds through tactile interaction. This physicality underscores the trust and familiarity between individuals.

Surface behaviors:

Breaching (leaping out of the water), tail-slapping, and spy-hopping (raising their heads above the surface to observe) are common, adding a celebratory flair to the event.

These behaviors create a visually and acoustically spectacular display, often lasting several minutes, before the pods either merge to socialize further or continue their separate journeys. The synchronized nature of the ceremony suggests a high degree of social coordination and mutual understanding, traits that align closely with human cultural practices like ceremonial dances or communal celebrations.

Significance of Greeting Ceremonies

Greeting ceremonies serve multiple purposes within orca society, reflecting their complex social structure and emotional depth:

Strengthening Social Bonds: Orcas are deeply social animals, living in stable, matrilineal pods that can span multiple generations. Greeting ceremonies reinforce the connections between pods within a larger community or clan, fostering cooperation and mutual support. These interactions are especially critical in resident populations, where pods frequently interact and share resources, such as salmon runs.

Cultural Transmission: Each pod has a unique set of vocalizations and behaviors, akin to cultural traditions. Greeting ceremonies provide an opportunity for younger orcas to learn and practice these pod-specific behaviors, ensuring their transmission across generations. This cultural aspect parallels human traditions, where rituals like dances or songs are passed down to maintain group identity.

Celebration of Milestones: Ceremonies are often associated with significant events, such as the birth of a calf or the reunion of pods after months apart. These gatherings have a celebratory quality, with orcas displaying heightened excitement and playfulness. For example, researchers have observed pods coming together in “superpod” gatherings—large assemblies of multiple pods—following a birth, where greeting ceremonies may precede extended socializing, foraging, or play.

Communication and Recognition: The vocal and physical components of the ceremony likely serve as a mutual acknowledgment of pod identity. Orcas use their unique dialects to distinguish between pods, and the ceremony may function as a formal “introduction” or confirmation of friendly relations. This mirrors human customs, such as exchanging greetings or performing rituals to affirm alliances or kinship.

Emotional Expression: The exuberance and coordination of greeting ceremonies suggest an emotional component, with orcas expressing joy, excitement, or relief at reuniting with familiar individuals. This emotional depth aligns with other documented orca behaviors, such as mourning, where individuals display grief by carrying deceased calves, as seen in the case of Tahlequah, who carried her deceased calf for 17 days.

Canada Killer Whale, orcinus orca, Female with Calf by Slowmotiongli

Parallels to Human Social Habits

The comparison to human social habits is particularly apt given the structured, communal, and celebratory nature of orca greeting ceremonies. Several parallels stand out:

Formalized Rituals: Just as humans engage in formal greetings—such as handshakes, bows, or ceremonial dances—to mark significant social interactions, orcas use greeting ceremonies to structure their encounters. These rituals convey respect, recognition, and shared identity, much like human diplomatic or cultural ceremonies.

Communal Celebrations: The celebratory aspect of greeting ceremonies, especially during events like births, resembles human traditions such as baby showers, weddings, or community festivals. In both cases, the gathering serves to strengthen social ties and share in collective joy.

Group Identity and Belonging: Orcas, like humans, derive a sense of belonging from their social groups. The pod-specific dialects and behaviors in greeting ceremonies reinforce group identity, similar to how human communities use language, music, or rituals to distinguish themselves and foster unity.

Emotional Connection: The emotional undertones of greeting ceremonies echo human expressions of affection and reunion, such as hugging loved ones after a long separation. The tactile and vocal interactions among orcas suggest a shared emotional experience, highlighting their sentience and capacity for complex feelings.

Scientific Observations and Context

Greeting ceremonies have been most thoroughly documented among the Southern Resident killer whales of the Pacific Northwest, a population known for its intricate social structure and frequent inter-pod interactions. Researchers from organizations like the Center for Whale Research and NOAA Fisheries have observed these behaviors during superpod gatherings, particularly in areas like the Salish Sea, where pods converge during the summer to forage on Chinook salmon. For example, a 2018 study noted that Southern Resident orcas engaged in greeting ceremonies lasting up to 10 minutes, with pods aligning in precise formations before erupting into synchronized displays.

Similar behaviors have been reported in other populations, such as the Northern Resident orcas of British Columbia and transient (Bigg’s) killer whales, though the specifics vary. Transient orcas, which lead more nomadic lives and form less stable social groups, may exhibit less formalized greetings, focusing instead on brief vocal exchanges or physical contact. These variations underscore the cultural diversity among orca populations, a trait that further parallels human societies.

The study of greeting ceremonies also ties into broader research on orca intelligence. Orcas possess large, complex brains (weighing up to 15 pounds) with highly developed neocortices, enabling advanced cognitive functions like problem-solving, communication, and social coordination. Their ability to perform synchronized behaviors in greeting ceremonies reflects this intelligence, requiring precise timing, spatial awareness, and an understanding of social cues. Additionally, their use of echolocation and pod-specific dialects enhances the complexity of these interactions, allowing orcas to communicate nuanced information during the ritual.

Orcas social bonding are so deep that they are dedicated to frequently support their fellow pod members, whether it’s helping injured individuals catch food or providing care for offspring well into adulthood. Orca grandmothers, even after experiencing menopause, continue to care for their grandchildren, further highlighting their strong familial bonds. Royal Society Biological Sciences, researcher Michael N. Weiss et al, – This 2021 study revealed that orca social bonds are comparable to those observed in primates, including humans. These bonds are especially pronounced among individuals of similar age and sex. The close companionship observed among distantly related young males suggests the presence of what can be described as friendship within orca pods.

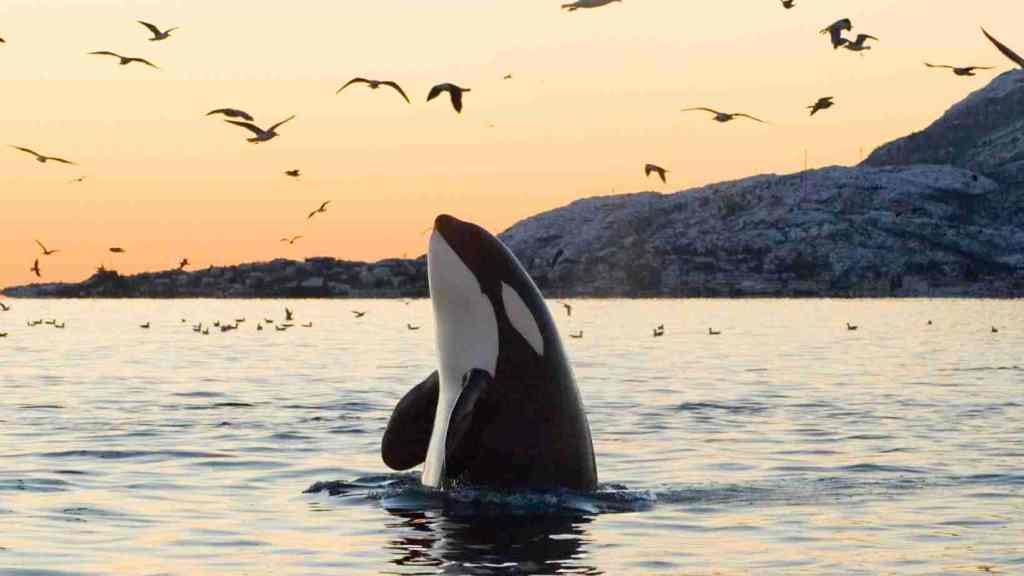

Big Orca Sunset by Sethakan

Orcas are social learners, and their capacity for social learning is highlighted by their occasional embrace of trends. These temporary behaviors, often initiated by just a few individuals, can catch on rapidly within their communities. For instance, in the 1980s, a group of orcas in the Pacific Ocean adopted the quirky habit of wearing salmon as headgear. What began with one female orca carrying a dead salmon on her head quickly spread to other pods in the same community. The short-lived trend exemplifies the orcas’ remarkable creativity and social learning abilities.

Orcas hunting by Ivan Stecko.

Orcas are adept at learning and employing specialized hunting techniques. For example, some populations in Argentina have learned to beach themselves to catch seals on the shore. In Antarctica, orcas create waves to dislodge seals from floating sea ice. Their hunting prowess extends to different prey types, from salmon in the Pacific to beaked whales off Australia and stingrays near New Zealand.

Killer Whale, orcinus orca, Female with Calf by Slowmotiongli from Getty Images.

The Tragic Case of Kshamenk, an Orca isolated most of his life.

Photo from Dolphin Project

Kshamenk’s tragic history is well-documented. At the time of his capture in 1992, he was believed to be around three or four years old and has since spent the last 30 years in captivity, isolated and alone. There are rumours that his stranding was orchestrated by boats with the intention of capturing him and other members of his pod under the guise of rescue, only to keep them as attractions.

Kshamenk, has lived at Mundo Marino since he was captured as a three-year-old after being stranded in Samborombón Bay on November 17, 1992, ( he should have been released back to the ocean). Reports from organizations like Dolphin Project and UrgentSeas typically place his birth around 1988 or 1989. Adding 32 years since his capture (1992 to 2025):

The Argentine government declared him unreleasable after his rehabilitation, and since the death of his tankmate Belén in 2000, Kshamenk has lived in complete isolation, deprived of any interaction with other orcas, this has caused immense cruelty and suffering to Kshamenk over the decades passed. As explained in this article Orcas are highly social creatures, and need to be with companions.

As a native species of Argentina, Kshamenk is legally under the ownership of the Argentinian government, granting them the authority to make decisions about his future. This government control was evident in 2001 when attempts to transfer Kshamenk to the United States were blocked by Argentine law. However, it was hoped the new administration might reconsider transferring Kshamenk to a sanctuary that has far better conditions closer to the wild, to allow rehabilitation, companionship and potentially move toward releasing Kshamenk back into the wild if possible, as many activists and petitions have long advocated.

Mundo Marino, the marine park where Kshamenk is currently held, does not own him and therefore cannot sell or transfer him. The responsibility for any decision regarding his future ultimately lies with the new Argentinian government. Activists have been pressing for Kshamenk’s release, citing the deteriorating conditions of his captivity and his worsening health. The Argentian government needs to be more receptive to these demands, potentially leading to Kshamenk’s release into a sanctuary or even his natural habitat.

Broader Implications and Relevance to Kshamenk’s Case

The social richness of greeting ceremonies highlights the tragedy of isolated captive orcas like Kshamenk, who has been isolated at Mundo Marino in Argentina for over 30 years without contact with other orcas. Orcas thrive on social interaction, and the absence of pod-based rituals like greeting ceremonies, likely contributes to the worsening condition of Kshamenk’s documented distress, evidenced by behaviors such as logging and staring motionless at his tank’s gate. His inability to engage in these natural behaviors highlights the cruelty of solitary captivity and strengthens the case for his relocation to a seaside sanctuary, where he could potentially interact with other orcas and experience a semblance of his natural social environment.

Moreover, the emotional and cultural significance of greeting ceremonies challenges the ethics of orca captivity more broadly. Facilities like Mundo Marino, which profit from keeping orcas like Kshamenk in isolated confined spaces, deprive these animals of the social and intellectual stimulation they require. Recognizing orcas’ capacity for complex rituals and emotional bonds, as seen in greeting ceremonies, supports arguments for their sentience and the need for legal protections, such as Argentina’s proposed “Kshamenk Law” to ban marine animal captivity.

Kshamenk Law

The proposed “Kshamenk Law” (Ley Kshamenk) in Argentina, aimed at banning marine animal captivity, emerged in July 2022. Specifically, it was introduced in the Argentine Senate on July 6, 2022, under File S-1577/22, as a bill to prohibit shows with marine animals, their captivity, and reproduction, except for rehabilitation and reintegration purposes. The initiative was driven by animal rights organizations, including Derechos Animales Marinos (DAM), and supported by Senator Nora del Valle Giménez. The bill was later filed in the Chamber of Deputies on October 6, 2023, under File 4131-D-2023, following over a decade of advocacy by groups like Activistas Animalistas de La Costa and lawyers such as Mauricio Trigo and Regina Adre. Public campaigns, including a Change.org petition launched in 2015 and gaining significant traction by 2021, also helped build momentum for the legislation.

Kshamenk’s distress is palpable, as he has been observed staring motionless at the tank’s gate “24 hours a day.” Orcas are highly social creatures that thrive on interaction with their peers, and Kshamenk’s isolation has undoubtedly contributed to his deteriorating condition.

“We are working alongside Argentinian activists and members of Congress to bring attention to Kshamenk’s cruel circumstances,” said a spokesperson for UrgentSeas. “He must be relocated from his small concrete tank to a place where he can be with others of his kind before it’s too late.”

Mundo Marino continues to benefit financially from Kshamenk’s misery. Though relatively unknown in the United States, the park has connections to SeaWorld, a company infamous for its exploitation of captive marine animals. Former orca trainer and author John Hargrove revealed that before SeaWorld ceased its orca-breeding program, they sent staff to Argentina to train Kshamenk for semen collection. His semen was reportedly used to inseminate at least two female orcas at SeaWorld’s U.S. parks.

The state of Kshamenk at Mundo Marino is heart-breaking. Like many captive male orcas, he has a collapsed dorsal fin—a condition rarely seen in the wild and often associated with stress or poor health. Video evidence shows Kshamenk engaging in a behaviour known as “logging,” where he floats motionless on the water’s surface, seemingly having lost all hope.

This distressing situation is not exclusive to Kshamenk. Visitors to Mundo Marino have shared disturbing footage with PETA, revealing sea lions suffering in inadequate enclosures without proper shade, leading to cataracts and fur loss. PETA’s Senior Veterinarian, Heather Rally, identified signs of stereotypic behavior among the sea lions, indicating severe stress.

Captivity in such restrictive environments leads to profound physical and mental suffering for marine animals. In the wild, orcas can live up to 80 years, but in places like Mundo Marino, their lives are significantly shortened. For the past 23 years, Kshamenk has been the only orca at Mundo Marino, endlessly circling a small pool with no social interaction. If the park does not release him to a sanctuary where he could experience a more natural environment, Kshamenk is likely to meet the same tragic fate as Milagro and Belén.

By January 2023, Kshamenk’s condition had visibly worsened, showing signs of malnutrition. Although, he gained some weight by December 2023, his overall health remains a significant concern. Yet, there has been no official statement from his caretakers or Mundo Marino, leaving his fate uncertain and at a critical point where action is needed to save Kshamenk’s life, he has endured far too much suffering for over 31 years and has clearly given up. A year and 11 months later efforts are still being made to get him out of this suffering condition to an open sanctuary where he can be with other orcas to socialise with, but nothing has changed to date.

Latest Developments

December 2024: A significant setback occurred when the Federal Court of Dolores, under Judge Martín Bava, rejected a precautionary measure to halt Kshamenk’s participation in Mundo Marino’s shows. The ruling was based on a veterinary and ethological report claiming Kshamenk showed no severe stress or health issues (beyond a broken tooth, which was not founded on the reality of his deteriorating health and behaviour) and that changing his routine could harm him. This decision allowed Mundo Marino to continue using Kshamenk in performances, frustrating activists who argued the report ignored evidence of psychological distress.

Public and Activist Efforts (2024–2025): Despite the court ruling, advocacy has continued unabated. Organizations like UrgentSeas, Dolphin Project, and PETA have sustained pressure through social media, with videos on TikTok and Instagram (e.g., a June 2024 drone clip by UrgentSeas) garnering hundreds of thousands of views. The Change.org petition remains active, though no updated signature count beyond 690,000 is available. Posts on X in early 2025 ( including my own) reflect ongoing calls for President Javier Milei to intervene, but no response from his administration has been reported

Legislative Status (April 2025): There is no evidence that the Kshamenk Law has progressed beyond its 2023 filing in the Chamber of Deputies. The bill has not been passed or scheduled for a vote, and its status remains stalled. The lack of updates from official Argentine government sources or the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development suggests legislative inertia, possibly due to competing political priorities or opposition from entities like Mundo Marino.

Conclusion

As of April 15, 2025, the Kshamenk Law, intended to ban marine animal captivity in Argentina, remains stalled in the legislative process, with no progress reported since its filing in the Chamber of Deputies in October 2023. Kshamenk, now approximately 36 or 37 years old, continues to languish in isolation at Mundo Marino, his health and mental state deteriorating as evidenced by behaviors like logging and prolonged inactivity.

The December 2024 Federal Court of Dolores ruling, which rejected a measure to halt his use in shows based on a veterinary report claiming adequate health, has further dimmed prospects for immediate relief. Despite this setback, activists from UrgentSeas, Dolphin Project, PETA, and Derechos Animales Marinos (DAM) persist in their efforts, leveraging social media campaigns and a Change.org petition with over 690,000 signatures to demand Kshamenk’s relocation to a seaside sanctuary. The absence of such facilities in Argentina, coupled with Mundo Marino’s resistance and the lack of response from President Javier Milei or the Ministry of Environment, underscores the urgent need for renewed political will and international pressure to advance the bill and secure Kshamenk’s freedom.

Despite what some say, it has been proven with release of captive orcas back to the wild they can relearn from their peers and lead a happy life thriving in the wild again.

Kshamenk has been confined in isolation for far too long in a tank in Argentina, without other Orcas as company, and without intervention, he faces a grim fate. The orca is in a critical state, trapped in a tiny enclosure that has taken a severe toll on his health due to his isolation. I had hoped that the change of political powers in Argentina would bring positive change for Kshamenk, despite my past efforts to draw attention to his long-term suffering and the efforts of other advocates for Kshamenk’s relocation to be in a more natural environment with other Orcas. However, so far President Javier Milei has ignored the situation of Kshamenk. Therefore, more needs to be done to help save Kshamenk’s health and improve the final years of his life. There is not much time if action isn’t so Kshamenk may be with other orcas in better conditions.

Kshamenk’s plight highlights the broader ethical crisis of orca captivity, where intelligent, social animals endure profound suffering in confined environments. His case demands immediate action to ensure he can live out his remaining years in a more natural setting with the companionship of other orcas, to experience their complex social rituals, like greeting ceremonies, and emotional depth demonstrate their sentience. To support Kshamenk’s cause, individuals can take action by:

Signing and sharing the petition: Visit the Change.org petition at change.org/p/liberen-a-kshamenk or start a new petition to demand his release to a sanctuary.

Following advocacy groups: Stay updated through UrgentSeas (urgentseas.com) and Dolphin Project (dolphinproject.com) for campaign developments and opportunities to engage.

Contacting Argentine officials: Reach out to the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development or local representatives to urge support for the Kshamenk Law and transparency on Kshamenk’s health. Contact details can be found at argentina.gob.ar/ambiente.

Raising awareness: Share Kshamenk’s story on social media using hashtags like #FreeKshamenk and #LeyKshamenk to amplify global pressure.

by

Consider a paid subscription to access my newsletters, books and podcasts or drop some magic beans at Ko Fi

References

UrgentSeas, “Kshamenk Campaign Updates,” urgentseas.com, accessed April 2025.

Dolphin Project, “Kshamenk: The Loneliest Orca,” dolphinproject.com, accessed April 2025.

Change.org, “Liberen a Kshamenk,” change.org/p/liberen-a-kshamenk, accessed April 2025.

Derechos Animales Marinos (DAM), “Ley Kshamenk,” derechosanimalesmarinos.org, accessed April 2025.

PETA, “Kshamenk’s Captivity at Mundo Marino,” peta.org, accessed April 2025.

Argentine Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development, argentina.gob.ar/ambiente, accessed April 2025.

Loved reading this information. Would love to know why they attack boats? Fisher people not letting them ‘breathe’ so to speak?